Uncharted 2: Among Thieves - Becoming a Hero

Drew Davidson & Richard Lemarchand

Published in Well Played 3.0: Video Games, Value and Meaning.

Ed. Drew Davidson. Pittsburgh, PA: ETC Press, 2011.

With this

essay, we’re going to unpack how the design of a game (Uncharted 2: Among Thieves) can offer players the chance to explore

and learn all the possibilities within the playing experience. In other words,

a good game can teach you how to play it through the very act of playing it.

And players can develop a literacy of games as they learn through the playing

of a variety of games.

With that in mind, Richard Lemarchand (Lead Game

Designer at Naughty Dog and Co-Lead Game Designer of Uncharted 2: Among Thieves) and I are going to explore the making

and playing of the game. We’re going to analyze sequences in the game in detail

in order to illustrate and interpret how the various components of a game can

come together to create a fulfilling playing experience unique to this medium. With

this paper, I wrote a complete first pass unpacking my gameplaying experience

(which included some discussions with Richard). Richard then added in his

thoughts and responses to my analysis, to which I, in turn, replied. So, the

bulk of the paper is from my perspective, but we’ve called out specific

comments from Richard and my replies. Throughout, we’ve tried to capture the

range of dialogue we’ve had around and about the game.

From a

gameplay experience perspective, we’re going to walk through how the game

design and narrative development unfold. To help track this process, we’ll

refer to two diagrams. The first diagram used is a classic literary plot

diagram.

Using

this diagram, we can follow the story of Uncharted 2 as it develops

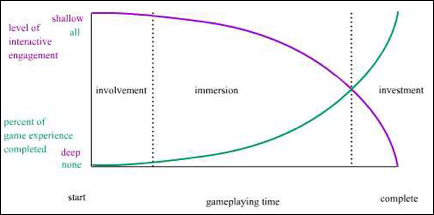

across key moments in the game. Next, we’ll use a diagram illustrating the

stages of interactivity.

This

interactive diagram was developed in a previous paper (Davidson 2005) and

outlines the interactive experience of playing a game. Briefly, the

experience is posited to have 3 stages: involvement – being initially

introduced into the game; immersion – becoming engaged with the gameplay

and the gameworld; and investment – feeling

compelled to successfully complete the game. The interactive diagram

illustrates these three stages. The x-axis shows the relationship of the

time spent playing the game, from start to completion. The y-axis shows both

the level of interactive engagement, down from shallow to deep, and the

percentage of game experienced, up from none to all.

Comparing

the results from both of the above diagrams helps to illustrate the

relationship between a game’s story and its gameplay and how they can fit

together to create a satisfying and engaging interactive experience. Of course,

this approach wouldn’t necessarily be the most apt for analyzing all the

different genres and types of games, but we think it works well for Uncharted

2.

One method that

isn’t directly explored is the procedural, computational nature of how this

experience is created. Michael Mateas (2005) and Ian Bogost (2007) have written

on the importance of procedural literacy, but for the purposes of this

interpretation, the focus is kept more on a gaming literacy (GameLab Institute

of Play 2007) and an exploration of the gameplay and narrative. Also, James

Paul Gee (2007) has written on thirty-six learning principles associated with

games, which illustrate how a game teaches us to play. And in performing this

interpretation, Bogost’s (2007) ideas on “unit operations,” as an analytical

methodology in which the parts of an experience are viewed as various units

that procedurally inter-relate together to create the experience as a whole, are

not explicated in detail, but combined with Gee’s ideas of learning principles,

inspire an exploration of how the gameplay and story can be seen as learning

units of meaning that inter-relate in a variety of ways and lead us to a

literacy and mastery through the playing experience (Davidson, Well Played,

2008).

Needless to say,

this article is full of spoilers on Uncharted

2 (and some for the first Uncharted)

so consider this your fair warning. While it’s not necessary, we encourage you

to play the game(s) before you read on. A goal of this article is to help

develop and define a literacy of games as well as a sense of their value as an

experience. Video games are a complex medium that merits careful interpretation

and insightful analysis. By looking closely at a specific video game and the

experience of playing it, we hope to clearly show how a game can be well

played.

Introduction

Uncharted 2: Among

Thieves is the sequel to the hit game, Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune. Released in

the Fall of 2009 for the Sony Playstation 3 (PS3), it

garnered critical acclaim (with a 96 MetaCritic score) and many game of the

year awards (plus it often came close to sweeping many award shows across all

categories). Within the world of the game, it develops on the experiences of

the first Uncharted as we join the

new adventures of Nathan Drake, the player character from both games. For the

scope of this paper, we won’t delve too deeply into details about the first

game, just enough to help explain any events and characters that span both

games.

Before we

dive into the game in detail, let’s start with a more high-level overview.

Naughty Dog was known initially for their Crash

Bandicoot and Jak & Daxter series

of games, and is a subsidiary development studio of Sony Computer

Entertainment. As a Sony subsidiary, all their titles are exclusive releases on

Sony platforms (currently the PS3). In 2007, they branched out with a new

title, Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune.

The game was a 3rd person action-adventure game that drew favorable

comparisons to the Tomb Raider video

game franchise in terms of gameplay and gameworld, and Raiders of the Lost Ark in terms of story and cinematic

presentation, and it was the sleeper hit of 2007. It should be noted that

Richard was the lead game designer on both of the Uncharted games (sharing lead

design with Neil Druckmann on the second).

In Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune, players play

as Nathan (Nate) Drake, a contemporary fortune hunter, and they join in an

adventure to find the lost treasure of Sir Francis Drake. This adventure leads

to a forgotten island in the Pacific, and Nate and his companions discover

clues, secrets, maps and more, that help them unravel

the mystery and find the treasure. Gameplay consisted of plenty of combat

(hand-to-hand and gunplay) as well as a lot of exploratory platforming as they

work their way through the exotic environments.

Uncharted 2: Among Thieves picks up

after the events of the first game. Drake is tempted back into this next

adventure with a new group of mercenary companions. Characters from the

previous game come to play a role in this adventure as well. Unlike the first

game, which takes place primarily on one island, this adventure takes Drake to

exotic locales all over the world on the search for the legendary Himalayan

valley of Shambhala.

Richard Lemarchand: When Drew invited me to add some remarks to a

paper he was writing about Uncharted 2:

Among Thieves, I was immediately interested in having the opportunity to

look at the game through a different lens – that of an analytical

review. Of course, since Uncharted 2 was released, my friends at

work and I have been studying the reviews that both critics and fans have

written, looking for insight into where we had been successful with the game,

and where there was room for improvement.

I have become increasingly interested in game criticism in past years,

as my understanding of how film and literary criticism works has expanded, and

I now see that a robust professional and academic critical context is an important

adjunct to the creative culture that produces games, and that advancement in a

form is rarely possible without it. I thought that Well Played 1.0, the

book that Drew edited and partly authored, offered fresh and interesting takes

on the games that it looked at, and I was curious as to what we would uncover

if we looked at our game in a new way.

My personal experience of Uncharted

2 had been intense and rewarding. The game took 22 months to conceive and create, and I was involved in

the process from before the beginning, as we began to discuss ideas for a

sequel during the closing stages of the first game in the Uncharted series, Uncharted:

Drake’s Fortune.

We had always imagined Uncharted as a series of games, and our contemporary reinvention of pulp adventure

tropes gave us lots of potentially rich subject matter. Our decision to push both cinematic

gameplay and character-driven storytelling beyond anything seen in videogames

before provided many challenges, but also the singularly most rewarding and

satisfying game development experience of my career. I’m excited to have an opportunity to

share a glimpse behind the scenes of the process in the course of Drew’s

narrative.

Full

Disclosure from Drew Davidson

In case it’s

not apparent, I should share that Richard and I are friends, and that helped

spur the idea for writing this paper together. In the past, I’ve approached the

analysis of a game mostly from my perspective as a player. Although, I recently

did an analysis of World of Goo, and

knowing Kyle Gabler (game designer) enabled me to participate in the beta

testing of the game as well as to ask a lot of questions. And last year at

Games + Learning + Society 5.0, I did a live play and analysis of 2008’s Prince of Persia with James Paul Gee and

Francois Emery, the lead level designer on the game. Francois

and I were introduced by a mutual colleague, and we prepared through

email, but we first met the morning of the presentation. The session went very

well, with a lot of shared details coming out during the playthrough in front

of the crowd. In fact, it led to an invitation to do a similar presentation for

the Games + Learning + Society 6.0 Keynote. I thought of asking Richard about

doing the keynote together, because I was excited about playing Uncharted 2, which in turn has led to

our writing this essay.

At the time

of this writing, I’ve only played through Uncharted about 1/4 to 1/3 of way through twice now. I started playing it during the

winter holidays of 2007, and was enjoying it, but ran into the start of spring

semester classes, and had to put it aside, and just didn’t get a chance to pick

it back up at the time. When Uncharted 2 came

out in 2009, I had the idea that I should go back and revisit the first game

before I jumped into the second, but on discussing this with Richard, he

encouraged me to play Uncharted 2 first

to enjoy all the new content and gameplay improvements they were able to put

into the second game.

Taking

Richard’s advice, I played through Uncharted

2 and completed it two times, while also playing some specific sections

several times (I have yet to take advantage of the multiplayer gameplay). I

then thought about starting the first game over again for the sake of being

thorough, but only got a little further along in the game before getting too

frustrated with the gameplay controls of the first game as compared to the

improved controls of the second game (more on this below). During my playthroughs, I visited

GameFAQs from time to time to double check to make sure I didn’t miss anything

major (although both games are fairly linear in their experience, so this

wasn’t too much of an issue). Finally, I should note that Uncharted 2 is one of the rare games that my wife enjoyed watching

me play from start to finish, as long as I was playing on the “Easy” setting

(and more on this below as well).

Narrative

& Gameplay Analysis

Now let’s do

a close analysis of the game. It’s such a large experience, that I’m not going

to cover everything that happens in great detail, but I do want to highlight

key points and sequences in the game that contributed to the overall experience

of playing.

Uncharted 2 starts with a bang that sets

the tone for the pacing of the story and gameplay, and how the two are blended in

the game through the use of what Naughty Dog calls IGCs (standing for In-Game Cut-scenes).

IGCs are intricate moments that combine real-time interactivity (or briefly

non-interactive but real-time rendered moments) with techniques from the

language of cinema. In a lot of games there are Quick Time Events (QTEs) that

are extended interactive cut-scenes in which a player has to press a button at

key moments in order to advance through the cut-scene event successfully.

Naughty Dog came up with IGCs as a term in order to help emphasize how the

in-game cut-scenes in Uncharted 2 are

more seamlessly interactive and integrated into the gameplay than a normal QTE.

In the first

moments of Uncharted 2, we find ourselves as Drake, coming to consciousness, wounded and bleeding, alone in a train car hanging precariously from a mountain in a roaring

blizzard. You then gain control

over Drake as you try to climb out of the train to safety. Throughout this

initial sequence are several IGCs that help introduce players to a highly

polished cinematic perspective meshed with integrated interactive gameplay

moments. So you have very short periods where you actually don’t have control

of Drake, but you watch sudden events happen and then immediately gain control

again. In this instance, the action comes to a climax with the train jerking

and sliding off the cliff, while you race to get out before it does. You start

getting a good sense of how the platforming gameplay works as you jump, swing

and climb. Climbing out of the train gives you a good introduction to all the

platforming mechanics. You work your way up and out, climbing the interior and

exterior as stuff falls on you, handholds break, and you finally make a leaping

run onto solid ground as the train goes crashing away below you.

Drake then

loses consciousness, and this leads to a more traditional and extended

flashback cut-scene that you get to watch. In this scene, Drake is at a beach

bar and is met by an old acquaintance, Harry Flynn, along with a femme fatale,

Chloe Frazer. They have a job (presumably the reason Drake is currently

unconscious on a snowy mountainside) and they want to rope Drake into joining

them. This job has something to do with some lost treasure related to Marco

Polo and his travels, and Drake is uniquely qualified as he is the only person

to have pulled off this particular heist. Drake resists at first, but slowly gets tempted into helping out, the

scene ends with them toasting to the adventure, and Drake saying, “What could

possibly go wrong?”

Richard Lemarchand: I was glad to see your remark, that the job that

Chloe and Flynn are offering in Drake is presumably the reason that he’s now

passed out in the snow in the Himalayas, because that was exactly the kind of

thing we wanted the player to think during the cutscene.

By showing Drake in a dangerous situation and an inhospitable

environment at the very start of the game, our normally empathetic, curious

audience starts to ask how Drake came to be in such a situation – even if

they’ve never seen him before. By

making our flashback cutscene start to tell the story of a chain of events that

might lead to Drake’s disastrous circumstances, we naturally grab and hold our

audience’s attention, right from the very beginning of the game.

This

definitely worked on me as a player, as I was instantly drawn into the action

(and what the heck has happened?). What could go wrong indeed. You wake up in control of Drake again, back on the icy cliffs in the middle of

a blizzard. And now you get your first sense of the combat gameplay. Like the

climb out of the train, this section of gameplay briefly introduces you to the

combat mechanics as you get a sense of how to use various weapons that are

strewn all around in the wreckage of the rest of the train along with some

soldiers who appear to be after Drake. As you work your way through the

wreckage from carriage to carriage, there are also explosions that rock you

around, and Drake loses consciousness again.

Which cues

up another cutscene that you get to watch. This one

shows Drake and Chloe together. There are hints that Flynn is actually onto

something real, and there seems to be a love triangle brewing, and some trust

issues amongst the three of them. The scene ends with Drake regaining

consciousness on the icy mountainside.

RL: In fact, as Drake regains consciousness we seized the opportunity

to add an interactive moment. When

control returns to the player after the cutscene, Drake appears to still be

unconscious. He is lying prone in a

smashed train car, with one arm slightly swinging, and his eyes closed. Only when the player touches the analog

stick will he start to stir and then stand up.

It’s one of those chances for us to give the player one of those “oh

cool, I’m back in control” moments. It might be a little fourth-wall-breaking, but players generally remark

positively on that moment of revelation as at least novel, and I think that we

can probably leverage that type of experience towards both gameplay and

storytelling ends in the future.

Interestingly,

I didn’t pick up on this initially, but did notice it after the fact. For me, I

was eager to get Drake back up and on his feet and start actively playing the

game. As you stumble back out into the blizzard, you come upon a unique looking

dagger. One that shows up spinning every time a scene loads in the game. So,

this dagger must be important (and in some way the reason behind all the

catastrophe on this mountainside). As Drake cradles the dagger, the scene fades

out, and then a new scene fades in, as you’re told that it is four months

earlier in Istanbul.

RL: One more comment about your not noticing that interactive moment when Drake regains consciousness: we’ve found that it’s often the case with this kind of interactive finesse: many players will never notice it. Some game developers will use “hardly anyone will notice that” as a reason not to put something in a game, and of course, you have to draw the line somewhere. But when an opportunity, like this one, takes relatively little effort to put into the game and doesn’t require the creation of new assets, I always jump at the chance to make our game even a little richer. Players also love the feeling that they’ve discovered a secret.

I’d also like to grab this opportunity to mention that Uncharted 2, like all of Naughty Dog’s

games since Crash Bandicoot, streams

data from the disc so that players only have to experience load times at the

start of a play session, and never during the flow of the game’s action and

story. This is very important for

us, in maintaining the pacing we’ve carefully constructed, which is so critical

to our creation of a cinematic experience that players get caught up in.

And this

definitely helps to create a more seamless experience of the gameworld and

story. So, you leave Drake on the mountainside, and back in time, you find him

in Istanbul with Harry and Chloe ready to run the heist they were discussing in

the first extended cutscene. Before I get into the details of this first heist,

I want to take the time to comment on the cinematic storytelling that has been

used to introduce you to this gameworld. On a high level, in terms of the plot

diagram, we’re still getting some great introductory exposition, but also with

hints of things having all gone awry (that’s a huge mess on the mountainside).

And I’d like to note that the game story is broken up into 26 titled chapters

(so far, everything discussed has been in Chapter 1: “A Rock and a Hard

Place.”) To help with orientation, I’ll refer to these chapters as we move

through the analysis of the game. Considering the interactive diagram, we’re

still firmly in the involvement stage, we’ve had some

initial practice with the platforming and combat, and have also been introduced

to how the IGCs work.

But that

doesn’t quite do justice to the highly polished craft in which all of this is

seamlessly blended together into an amazingly engaging and gripping experience.

The IGCs are used to great effect, and you’re able to watch and play your way

into this gameworld. Naughty Dog has crafted the videogame equivalent of a

thrilling action adventure movie. Pushing this comparison deeper, they’ve used

the narrative conventions of these types of movies to help shape the story

beats as they play out across the game (which I believe helps make it such a

watchable experience). Story beats are the smallest units of a story, like an

exchange between characters in a scene, that advance the narrative, and this

initial sequence really does drop you right into the action. You then have some

flashbacks to help break up the tense action, but also to start filling in some

backstory on how it all started and how wrong things went awry. Simultaneously,

you’re gaining a sense of how the gameplay mechanics work as you play through

the scenes, establishing how you, as Drake, are able to survive the straits

laid out before you. The game pulls you into the story by requiring you to play

through it successfully (as the hero in a movie would do as well).

And now

you’re back in Istanbul four months prior, at the start of it all. From here,

the high-rolling, globe-trotting adventure kicks into

gear. You’re here to steal an artifact from a museum that should provide you

with a clue to the ultimate treasure you’re seeking. Chloe is the driver for

the escape post-heist, and Harry and Drake go through the sewers to enter the

museum from below. This is the beginning of Chapter 2: “Breaking and Entering,”

as you make your way through the museum to the

artifact. There are some interesting dynamics to this chapter that again blend

gameplay and storytelling well. For instance, Drake makes it clear that he

doesn’t want guns involved so as not to risk accidentally killing the innocent

museum guards. This gives you some sense of Drake’s character and motivations,

while also setting up a level that is more about sneaking around than shooting

it out. Harry has brought two tranquilizer guns though, so you can shoot some,

but your focus is more about traversing through the museum while remaining

undetected.

That said, there is a contradictory moment in this level where it

appears that Drake actually kills a guard. He is hanging from a ledge high up

on the roof of the museum, and a guard walks by, and the game prompts you to

hit a certain button, which causes Drake to grab the guard and toss him off the

roof to his apparent death. I’ve seen online that this moment disturbed players

in terms of their sense of who Drake is and what he would, and wouldn’t, do (Wardrip-Fruin,

2010).

RL: We were, of course, very focused on preserving the idea that Drake

didn’t want to take any innocent life during his time in the Museum. When the level’s layout offered us the

opportunity to showcase our “pull an enemy off a roof” stealth mechanic (one of

a number of new “action-stealth” moves that we’d added to Uncharted 2) we couldn’t resist seizing it, but we still didn’t

want Drake to appear inconsistent.

So we made sure that there was water below the roof for the guard to

fall into, and even went so far as to create an animation that showed the guard

swimming to safety, having survived the fall, and clambering onto a nearby rock

to recover.

However, we now realize, based on what we’ve read on the Internet,

that many players don’t notice that the guard survives the fall, and they think

that Drake has suddenly stopped caring about whether the guards get hurt. It’s

just one of those times where we have to realize that what we added doesn’t

“sell” or “read” – it’s not completely, transparently obvious to nearly

every player – and we just have to chalk this one up to experience and

try not to make the same mistake next time!

To be

honest, this moment didn’t register strongly with me at the time I played

through it, but I can see how players may not have “read” Drake’s intentions.

Moving on, Drake and Harry continue through the museum. Before we get to the

treasure, I want to unpack how this buddy system works on two levels. In terms

of story, you get to listen to the two characters banter back and forth while

they’re together, so it helps to establish their relationship for the player.

In terms of Drake and Harry, you get the sense that while they don’t fully

trust one another, they do have a camaraderie in which they joke with each

other. The dialogue pulls you into the characters in terms of content, but also

in terms of delivery. The voice acting behind the characters is excellent and it’s obvious Naughty Dog took great care in making sure the

characters come across in the voices. Granted, often their dialogue is

reminiscent of Hollywood blockbuster action movies, but that is the genre

they’re emulating, so it fits fairly well to the adventure in which you find

yourself as Drake. And on a gameplay level, the buddy system is used to help

keep you on the right track. Throughout the game, you’re almost always with a

companion (here it’s Harry) and this buddy often is able to serve informally as

a guide to lead the way so that you don’t spend too much time getting lost, and

also to give hints when you’re trying to solve environmental puzzles that

always seem to require two people (like boosting Harry up to grab a ladder that

he can then drop down to you). Once again, Naughty Dog is working with a high

level of integration throughout the experience.

Drake and

Flynn get to the treasure (and ancient oil lamp) that has a resin the burns

blue and enables them to read a scrap of paper from the lamp, that tells of a

tsunami that left Marco Polo shipwrecked in Borneo and the first hints that

Polo may have found Shambhala (Shangri-La) with the help of a cursed Cintamani

Stone (that may actually still be on a prominent mountain in Borneo).

So now they

know roughly where in the world they need to go next on this adventure. But

here the subtitle of the game (Among Thieves) really comes to the fore as Harry

double-crosses Drake, leaving him stuck in the museum while also setting off

all the alarms. So now you have to try to find some other way to escape, and

you can manage to get out of the museum through the sewers, but when you exit

you find yourself surrounded by armed guards.

RL: The characters that accompany Drake through the game are crucially

important for creating an emotional reality for the player, and we think that

it’s this emotional reality that makes our game engaging. We use the characters that Drake

interacts with to show different sides of his (often conflicted) character, and

we work hard at every stage of the process – from their character

designs, to our scriptwriting and performance capture processes, to the

implementation of the characters in gameplay – to make sure that the people

in our game are believable and nuanced in their characterization. We try to use techniques that are both

narrative and interactive to set up and pay off situations that deepen and

enrich the world of the game.

And I found

the character interactions definitely helped flesh out the world and where you

thought Drake stood within it. Three months later, you find that Drake is

(still) in jail. Victor Sullivan (Sully) shows up to spring Drake. Sully is

Drake’s friend from the first game. Their friendship was called into question

throughout that earlier adventure, but it all turned out to be a

misunderstanding, and Sully is one of the few people Drake trusts.

RL: We think that Nate probably mostly trusts Sullivan, but I

don’t think he trusts him completely. The world that Drake and Sully exist in

rarely allows for certainty about anything, and we try and use that to our

advantage whenever possible, to heighten the mystery, wonder and romance of our

game’s world.

This is

definitely taken advantage of as the reunion is complicated by the fact that

Chloe is with Sully. As they dance around regaining some trust, it is revealed

that Harry and his client (Lazarevic) have found Marco Polo’s lost boats in

Borneo, but have yet to find the Cintamani Stone. So, Sully, Chloe and Drake

team up to try to go to Borneo to sneak the Stone right out from under Flynn

and Lazarevic.

Off to the

jungles of “Borneo” (Chapter 3), and in this part of the adventure you partner

up with Sully. As you work you way into the jungle toward the camp, the stakes

are raised as you now get into more deadly firefights with Lazarevic’s men.

This is where you really get familiar with the combat gameplay mechanics with

multiple encounters and a variety of weapons from which to use. At the same time,

you’re also becoming more adept at traversing through the territory in which

you find yourself. Chloe is acting as a double agent getting in close to help

create a diversion and give Drake and Sully an opportunity to get access to all

of Lazarevic’s notes, journals and plans (in Chapter 4, “The Dig”). This helps

them realize that Lazarevic is off track in looking for the treasure. So, they

have a chance to find it, as soon as they shoot their way out of the camp.

Stepping

back for a second, this is where the story really aligns with action adventure

movie blockbusters from the past, particularly Raiders of the Lost Ark. You can definitely see the similarities

quite clearly, but it also helps you fall into the role of Drake. The familiar

story beats give you a direction of how you should act if Drake is indeed the

hero of this adventure. This in turn, aligns with your game goals as you play

your way through the experience.

Back in the

game, Drake, Sully and Chloe manage to find the resting place of the ancient

survivors deeper in the jungle. They don’t find the Cintamani Stone though, instead they find the unique dagger (a Phurba) from

the earlier scene on the mountain, which appears to be some sort of key to Shambhala

which they now figure out is in Nepal. And then Chloe fulfills her double agent

role twice. First it appears she turns Drake and Sully over to Flynn, but then

it becomes clear that it was to help save them and gives them a chance to

escape. And as the flee, we get a scene straight from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid as Drake and Sully leap from a

cliff into a raging river below and float away free and clear.

RL: We hope that we don’t draw on any preexisting narrative too much,

and we are always walking a fine line between appealing to adventure stories

from the past, whether it’s the more recent past of 80s action movies or the

distant past of Robert Louis Stephenson, and approaching everything with a

fresh eye that invigorates the characters and prevents them from feeling like

clichés or types. It’s always a

compliment to be compared to films as beloved as Raiders of the Lost Ark or Butch

and Sundance, though!

From my

perspective as a player, the familiarity of the story conventions helped draw

me into my (or Drake’s) role within the adventure. Speaking of which, now it’s

off to Nepal to try and find Chloe and the Cintamani Stone. At this point,

we’re solidly into some rising action on the plot diagram with the major

conflict coming into better focus (although I’m still not sure who I can trust

or not). And we’re getting solidly immersed in the interactive experience. The

last escapade gave you a lot practice in gameplay (both combat and platforming)

and at this point I’ve noticed I’m much better at both. I’m more accurate with

my gunplay, and more strategic about taking cover. And I’ve learned to adjust

the camera view to search around my environment to help find my way when I need

to jump around and climb.

The

experiences in Nepal last for several game chapters as we start with Chapter 5,

“Urban Warfare,” and it lives up to its title right away. As Drake is driving

through the war-torn streets, it’s apparent that the city is overrun with

fighting. And we get to see a classic Naughty Dog gameplay sequence in which

the perspective shifts and you have to run toward the screen. This is something

they’ve done across many of the different games they created. It adds a unique

control moment as everything is reversed, which adds an intensity to the gameplay as you have to adjust to the backward perspective

and controls on the fly. In this case, Drake ends up running down an alley with

a large military truck barreling after him. You have to run forward while

shooting backward in order to cause the truck to crash as you flee from the

wreckage in the alley. The switch of perspective makes it a challenging

gameplay experience that adds to the cinematic action of watching as a truck

comes bearing down on you. It’s another great sequence that makes you feel like

a hero when you survive (although truth be told it took me several tries before

I did).

There are

some other interesting gameplay twists that happen in Nepal. Right after the

alley sequence, you’re on your own for a bit before you find Chloe. So for

almost the first time in the game, you’re not buddied up with someone. This

increases your immersion as you have to find your way

on your own. Once you meet up with Chloe, the two of you work your way through

the war torn city, traversing alleys and up and down buildings. There is a nice

mix of platforming and combat as many of the buildings have been bombed or

damaged, and there are soldiers and guerillas all around.

There’s also

an interesting story moment on the roof of a hotel that happens to have a pool.

You’re up there to scout for the right temple in this city full of temples, but

you can have Drake jump into the pool, where he goofs around and jokes about

playing the Marco Polo game. This shows a great level or attention to detail by

the developers. Unlike many of the more sandbox, emergent games (like the Grand Theft Auto franchise) where

players have an open world to wander around in, Uncharted 2 is linear in progression, so you’re always moving

forward through the experience. But little moments like the pool scene open up

the gameworld and make it feel fully fleshed out, and you’re just moving

through it on your adventure.

RL: It’s always very satisfying when players call out this moment as

enjoyable, because it was a particular labor of love for a number of us,

including the actors who partly improvised the dialog and the game designer who

carefully added the dialog to the game and made this implementation interactive

– there are different dialogue flows dependent on whether the player

keeps Drake in the pool for a while or makes him climb out quickly. We even went so far as to re-jig our

Trophy scheme at the eleventh hour, adding two Bronze Trophies: one for when

Drake first jumps in the pool and yells “Marco”, and another one for the player

who keeps Drake in the pool long enough for him to get Chloe to say “Polo”!

I’ve enjoyed

how trophy schemes have developed to help track a variety of player

achievements across a game, this provides players with another level of

motivation to fully explore a game. And I really like how there are trophies

for little narrative moments like these. It encourages me, as a player, to

explore the world some more, which resonates well with the theme of game

overall. And so, shortly after the pool, Lazarevic finds out that Drake is in

the city, and sends out attack helicopters to deal with Drake. This leads to an

amazingly cinematic gameplay sequence. You and Chloe are trapped high up in a

building with soldiers chasing you from floor to floor, when a helicopter joins

in the fight and starts shooting missiles at the building. As a player it was a

confusing experience. I was in an office room using a desk as cover as soldiers

entered the room, when the perspective started shifting and all the furniture

and people started tumbling across the room as the building tilted. I wasn’t

sure what was going on, but noticed I was sliding toward a window and could see

that we were crashing toward the building next door. It all felt crazy, but I

made a run for it with Chloe and we jumped through the window, landing in the

adjacent building. And then it jumps to a quick IGC as Nate and Chloe turn back

and watch the other building collapse completely. This is definitely an intense

moment that made me feel like a hero. I was psyched to have survived (and

actually managed to do it on my first try) and was impressed by how the

designers created the gameplay sequence to line up with the story beats and

enable me to perform like an action adventure hero.

RL: This sequence was very important for us – it was among the

first of our major cinematic set pieces that we polished, and it showed off a

system that represented an important technical leap forward for us: our Dynamic

Object Traversal System. This

system let Drake, and all his enemies and allies, use all of their moves on any

arbitrary moving object in the world, and without it we couldn’t have realized

either this collapsing hotel, or other emblematic sequences like the Train

level. A system like this is pretty

much the Holy Grail for character-action game designers, since it lets us do

things we’d only previously been able to dream about, and it was incredibly

difficult to implement, causing our programmers to change or touch almost every

core system in the game. We felt

that the sequence was very successful, and it inspired us to push ourselves

ever further with our set pieces. It certainly seems to make an impact on players, and it was planned to

punctuate the peak of action that this part of the game reaches.

What’s

important to consider is how seamless the playing experience was. It makes me

realize that the technical challenges going into the Dynamic Object Traversal

System paid off as I didn’t even notice them (which meant I felt like I was

able to play the set piece (and feel like a hero) even in the chaos of a

collapsing building. Staying with this concept of being a hero, shortly after

escaping the collapsing building, Drake and Chloe run into Elena Fisher and a

cameraman (Jeff). Elena is a gutsy reporter from the first Uncharted, and through those earlier adventures Elena and Drake

developed complicated feelings for one another. Chloe argues to leave them on

their own, and Elena and Jeff seem a bit wary of joining Drake and Chloe. Based

on previous experience, Elena assumes that Drake is up to something (and most

likely it’s no good). Drake insists that they could use their help, so he talks

everyone into sticking together. What I liked about having this short story

experience shortly after feeling like such a hero jumping from a collapsing

building, is that it underlined for me that being a hero isn’t just about those

feats of derring-do, it’s also about doing the right thing. And you see Drake

stepping more into the role as a hero in this moment.

So, you now

have a party of four, deep in a city surrounded by enemies out to get you. As

you make your way through the violence around you, Elena reveals that Lazarevic

is a psychopathic war criminal, and she’s here to expose his war crimes to the

world (so now you know who you’re up against). The group works it way the to

right temple, and then there is some amazing environment puzzle solving within

in the temple that requires a lot of platforming by Drake as he uses his trusty

notebook and works to unlock the clues found within and beneath the temple

(Chapters 8 and 9). Once you successfully negotiate the puzzle platforming, and

use the Phurba as a key, you’re shown the location of Shambhala deep in the

Himalayas.

Of course,

Lazarevic’s men find you, and you have to fight your way out. In the ensuing

firefight, Jeff’s get wounded pretty bad, and Drake

has to help carry him away. This adds a gameplay wrinkle as well since Jeff

really slows you down, so you have to work at a much slower pace. Again, this

is combined with a story element as Chloe argues to leave Jeff, but Drake

insists on carrying him. And once

again, it looks like Chloe turns on you, as Flynn shows up, and we finally get

to meet Lazarevic. Although it looks like Lazarevic suspects Chloe and has her

taken her away to the train. He then kills Jeff and threatens Elena in order to

get Drake to share what he’s discovered. Once he has the information, Lazarevic

leaves and asks Flynn to kill them. Elena and Drake manage to get away and head

to the trainyard to rescue Chloe from Lazarevic.

RL: I’m not sure that I agree with your characterization of Drake at

the meeting with Elena and Jeff as heroic, at least not at the start, but this

scene is certainly a pivotal one for him. We use this moment to reset the rhythm of the action, and we do it

somewhat at Drake’s expense (and perhaps partly to his credit).

For a start, Elena openly challenges Drake about the nature of his

quest, saying, “So let me get this straight: you’re competing with a

psychopathic war criminal for a mythological gemstone?” In a single sentence we say everything

we need to about the breakdown of any romantic relationship that may have

formed between Nate and Elena at the end of the first Uncharted game, and we characterize Nate, rather negatively, as both a

criminal and a dreamer. We’ve

grounded our story in the context of the real world (or at least, a real world) and we’ve moved both Drake

and Elena’s characters forward a step in their relationship.

Secondly, this is the first time that Elena, a woman for whom Nate may

have had deep feelings, meets Chloe, Nate’s sexy sort-of current lover. Amy

Hennig, our Creative Director and head writer, says that this scene was one of

the most difficult to write in the whole game, and commentators have paid us

the compliment of remarking that many games – indeed, many films –

would have played this scene badly, perhaps showing Drake as swaggering or

cocky as his conquests past and present cross paths, and leaving all the

characters stuck playing out banal stereotypes that do nothing to honor them.

But instead Drake seems awkward and embarrassed – it betrays a

kind of vulnerability that I think is appealing, and also indicates that he’s

not just a regular Joe in terms of his sloppy fighting style and frequent

clumsiness: he can be conflicted and self-conscious, just like the rest of

us. The women are confident and

funny in counterpoint to Drake, and even seem to rather like each other, even

in the midst of a difficult situation.

So I think that the scene works tremendously well, not just to tamp

down the pace of the game after such an intense crescendo of action (and before

a relatively sedate sequence of exploration and puzzle solving in the Temple

complex), but also to shed some new light on the characters and the

relationships between them, and to bond the player to Nathan Drake as a likable

guy with some serious flaws.

I would

agree, that within this scene Drake isn’t necessarily heroic. But for me,

having him being awkward also read as a moment where he was

having to assess what he’s doing and why he’s doing it, and that got me

thinking that in order for Drake to become a hero, he has to figure out how to

do the right thing. We’re now at Chapter 12, and looking at the plot diagram,

we’re well into the conflict of rising action, so this mirrors the conflict

Drake is displaying in this scene as well. I’m feeling empathy with the

characters and want Drake to help thwart Lazarevic and save the day. In terms

of interactivity, I’m solidly immersed in the gameplay. I’m at the point where

I don’t even have to think about what buttons to push. For the most part, I’m

able to maneuver Drake as I need to, and now the designers do a nice job

throwing another wrinkle into the mix.

With Elena’s

help, and a lot of improvising with many different vehicles, you’re able to get

onto the train for a thrilling extended action sequence in Chapter 13. Plus if

you recall, the game began on a wrecked train on a snowy mountainside, so even

though you’re down in the valley, this very well might be that train since

Lazarevic knows Shambhala is up in the mountains. Now Drake has to work his way

through, under, over and around the train as he makes his way forward toward

Lazarevic, Flynn and Chloe. The train is a limited spatial environment so you

have to be careful (plus you can fall or get knocked off). And this train is

loaded for war; there are soldiers, weapons, tanks and helicopters. This is one

of the longest combat sequences, although because you’re goal is to get to the

front of the train, there is a lot of platforming as well. And the combat is mixed

up as well, as you have to take on soldiers in train carriages, on top of the

train, on the sides of the train as well as helicopters flying beside the

train. Plus the environment the train is moving through comes into play. You

have to watch out for, and avoid, signs near the side of the train and also for

signals above the train. And then the next thing you know you’re in a long

tunnel and you come out in the mountains (uh-oh).

Drake

finally finds Chloe, who asks him to leave. As they argue, Drake

gets shot by Flynn. Then Chloe starts arguing with Flynn and Drake is

able to run to another carriage followed by some soldiers. Wounded and trapped,

Drake takes aim and shoots some propane tanks, setting off some huge

explosions, and causing a massive train wreck.

We’re now

back at the same sequence that started the game. Recall, the game up to this

point has essentially been an extended flashback from the start of the game.

And once again, we have to climb Drake back out of the train again. And then fight

your way through the exploding wreckage and surviving soldiers out to get you.

You manage to get out and away, but now you’re basically wounded and lost in a

blizzard on a mountain. Drake collapses in the snow and

someone walks up to him as he loses consciousness (again).

RL: It’s good to read your remarks, here. It was easy for even us on the team to

forget that nearly the first half of our game takes place in flashback (when

viewed in a certain context, at least).

Non-linear temporal flow is a hallmark of some of my favorite films,

from Rashomon to Lola rennt to Memento. Indeed, discontinuity of space and time,

bridged by the edit, is a character of nearly all film.

I think that, partly because of pragmatic issues to do with camera

control in third-person character-action video games, and partly because we

perceive a relationship between digital games and digital simulations, both

developers and players are somewhat over-focused on maintaining temporal and

spatial continuity in narrative video games.

Few games have taken advantage of the opportunities offered by

thinking about time and space as the plastic, collapsible continua that they

are in cinema. When we remember

that games are different from simulations, new creative possibilities open up,

and I’m happy that the talented team members that came up with the temporal

sequencing of our game did so.

As a player,

the non-linear way the story is revealed created a more complex set of

expectations in terms of how I was experiencing the set pieces across time and

places. In the back of mind, I always had this feeling that I was heading for a

catastrophe on the side of the mountain, so I was paying attention to the

choices and consequences of Drake’s actions. Moving forward, Drake comes to in

a small hut with a small girl looking at him, and the man who rescued him. The

man speaks to Drake in Tibetan, which Drake doesn’t understand, but he notices

that his wounds have healed. We’re now in Chapter 16, it feels like we’re both literally and metaphorically getting close to reaching

the climatic moment in the story. And I’m starting to feel invested in the

gameplay experience. I want to find Shambhala and keep Lazarevic from ruining

it.

The Tibetan

man beckons Drake to follow him out of the hut. Which starts a short sequence

that has a similar effect to the earlier game of Marco Polo in the pool. As

Drake exits the hut he finds himself in a Tibetan village, he can follow after

the Tibetan rescuer, or walk around and play soccer with some kids and pet a yak.

Again, what’s nice about these little moments is that you don’t have to do any

of them, but if you do, you can feel more of the world in which you find

yourself. Also, in talking with Richard, he related how they designed these

particular moments so that players couldn’t go around and punch the villagers.

Instead, those familiar button presses lead to Drake offering handshakes or

waves of hello since Drake doesn’t speak Tibetan.

RL: Indeed, the idea for those hand-shaking interactions emerged

directly from playtesting. I was in

charge of the “Peaceful Village” level, and I noticed that about half of our

playtesters ran straight up to the villagers and threw a punch at them when

they arrived in the Village for the first time. By talking to them afterwards I worked

out that they weren’t really trying to hurt the villagers – they wanted

to test the bounds of our system, by attempting an interaction with the

world.

Experimentation of this kind is a fundamental aspect of the way that

players relate to video games – they make hypotheses about the game and

then test them out, and by doing so they learn the rules of the game and how to

succeed. Video game players are a

lot like scientists investigating a world in this regard.

We’d initially set up the villagers so that if Drake threw a punch at

them, nothing happened. Games that

reward experimentation on the part of the player with reactions that are

interesting or entertaining are generally considered better than those that

don’t, and so we decided to make the extra effort to add a set of animations to

show Drake and the villagers shaking hands or waving to each other, should the

player try to throw a punch at a villager. I’m still very grateful to the animators and programmers who expended

elbow grease on this.

It’s a moving experience whenever I hear that a player was delighted

when they found themselves shaking an old man’s hand or patting a yak on the

nose. It feels like the realization

of a playful dialog between the player and me, the designer.

And building

on the earlier scene with the pool, players have been encouraged to explore, so

it’s likely that they’ll encounter these unique interactions, which again

enhances and expands the feeling of the world in the game. Back in the village,

the Tibetan rescuer leads you into a house, and lo and behold, there’s Elena

(who speaks Tibetan to boot!). She followed the tracks from the train wreck and

found Drake. Elena introduces Drake to Karl Schafer, and older man who went on

an earlier expedition to find Shambhala. Schafer introduces Tenzin (the man who

rescued Drake) and shares some advice and warnings learned from his

experiences, and lets Drake know that the phurba is the key to Shambhala, so

Lazarevic is going to be coming for it. He also relates how the Cintamani Stone

will give Lazarevic great power to rule the world. During this conversation,

Drake wavers about doing anything more, he feels like it’s all been a big mess

and actually says that he’s through playing the hero. Elena argues that they

should try and stop Lazarevic, and Schafer offers to show Drake proof by having

Tenzin take Drake into the mountains to the remains of Schafer’s earlier

expedition.

RL: In terms of Joseph Campbell’s monomyth as reconfigured by Chris

Vogler in his screenwriting book, The

Writer’s Journey, this is a moment where Drake makes his final and most

emphatic refusal of the call to adventure. It’s a low point for Drake’s character, and an important point for us,

as it helps us show that Drake isn’t a straightforwardly crusading altruist. He

doesn’t want to get killed in the service of some abstract, even

ridiculous-seeming, quest. His

world is a serious, dangerous place – just like ours – and he’s a

sensible guy – someone just like us. Having Drake pass through this moment – where he simply can’t

accept that he’s a hero – grounds his character is reality and helps us

to relate to him.

This

underscored how Drake really struggled with doing the right thing (which is

more important than “playing the hero”). So, Drake now buddies up with Tenzin

and heads off into the mountains for Chapters 17 and 18. You make your way into

a mountain cave system, where you start finding some of the dead men from

Schafer’s expedition. There is a lot of platforming gameplay here with Tenzin

as you make your way through the icy cave system. You also start getting hints

that there is some sort of monster in the caves with you, and then you’re attacked by a ferocious yeti. Together with Tenzin,

you are able to fend of the beast, and continue deeper into the caves. Soon you

come upon a huge underground area with large statues. This leads to another

intense sequence of puzzle platforming as you work your way through the

environment with Tenzin. They then discover more dead men, and find out they

were Nazis after the Tree of Life and immortality. And it’s apparent that

Schafer killed the Nazis to prevent them from succeeding in their quest.

This

discovery significantly raises the stakes of our current adventure, and it is

followed with an attack by a bunch of the yetis. So Tenzin and Drake have to

fight them off and escape by activating an ancient elevator that gets them

above ground away from the monsters. From their perch in the mountains, they

can see that Tenzin’s village is being attacked.

So they rush

down into the village and into Chapters 19 and 20. They find Elena, who

confirms that Lazarevic has found them. Tenzin is worried about his daughter

and Elena tells them that she is hiding with Schafer, before telling Drake that

this terrible destruction that has been brought down on the Village is all

their fault – people are dying because of Drake and Elena. Drake and

Tenzin head out to find Schafer and Tenzin’s daughter, only to run into a tank,

which then pursues them through the village. This leads to an out-of-control

action sequence as you and Tenzin play cat and mouse with the tank. One moment

stands out in particular for me, it reminds me of the scene in the Bourne Ultimatum in which Bourne is

chasing an assassin through the medina in Tangiers. Except in this game scene, I’m running

with Tenzin, trying to keep some houses between us and the

tank. And there’s this intense moment, when the tank actually crashes

through the walls of the house that we’re running through.

In this

moment, a quick (all of a couple of seconds) IGC shows Drake getting bowled

over by crashing tank, but the camera angle during the IGC is such that I’m

instinctively trying to guide Drake out of the room, so when I do regain play

control, I’m already heading in the right direction. This is some very clever

design as it makes me feel as if I’m playing through the short IGC, while also

using the IGC to up the intensity of the moment. I’ve talked to some friends

who wondered if they were actually in control at all or not, but for me, it all

lined up. Yet another moment where I felt heroic in

performing some crazy feat of action.

Drake is

able to take care of the tank finally, and Tenzin finds his daughter, but

Lazarevic’s men have taken Schafer away with them in a convoy of trucks. Drake

and Elena manage to hijack the last truck and take off in pursuit and into

Chapter 21. This leads to a gameplay sequence somewhat like the train, but

ramped up a level, as you now have combat while also jumping from truck to

truck across crazy terrain.

RL: This long sequence, leading from the peaceful village to the ice

caves to the frozen temple and then back to the now-besieged village is a

pivotal section of the game. As

you’ve identified, there’s a lot going on there, in terms of cinematic gameplay

– sequences where complex set pieces play out almost entirely in

gameplay, with the player directly in control of Drake nearly all the

time.

We switch things up a few times, using moments of constrained gameplay

in a narrative way – like the climax of the first encounter with the

‘yeti’ – and we pull out every single trick in our bag to guide and

sometimes push the player from A to B to C, using ‘characters’ like the tank or

the transformed village to effect moment-to-moment emotional change in the

player. We even sucker-punch the

player a second time, having already brought Drake low by his near-refusal to

continue with the quest, by having Elena blame him for the awful transformation

of the formerly idyllic community.

But Tenzin occupies the heart of this sequence, of course. Drake and Tenzin do not share a common

language, and that gives us an opportunity not only for a few gags, but also

for the player to become bonded to this unusual, dynamic character almost

entirely through their collaborative gameplay actions. As Tenzin sets up ropes for Drake to

swing on, boosts him up to otherwise inaccessible ledges, and catches him as he

is about to fall to his death, we hope that a connection is slowly growing

between Tenzin and the player (or Drake, by proxy) in a way that the player

barely notices.

When Tenzin’s village comes under attack – and his small

daughter’s safety is in doubt – we hope that the groundwork we’ve

carefully laid gets activated, and that the experience of fighting through the

war-torn village is charged beyond what might expect from even the most epic,

awesome battle scene in another video game.

Interestingly,

I really wasn’t thinking about Tenzin specifically during this (he was just

another buddy as I was playing) but I really felt the responsibility of causing

the attack on the village and putting everyone’s lives, especially Tenzin’s

daughter, at risk.

RL: I should be clear in saying that the effect we were trying

to have wasn’t one that the player would, or should notice, and it is

interesting that you weren’t really thinking about Tenzin during this

sequence. Either we did our job

really well, or what we did with Tenzin didn’t make much difference! I do think this sequence would have had

far less – or perhaps just different – emotional impact if you’d

played through the Ice Cave with Chloe or Elena.

I would

agree that playing through with Tenzin gave it a better context in which to

have that emotional impact. Again, I felt like I needed to step up and do the

right thing. Back in the game, Drake and Elena end up getting forced off the

pass and over a cliff. The soldiers assume they’ve died, but Drake and Elena

(of course) survive and climb up and follow the convoy on foot to a monastery.

Spying from afar, they see the Lazarevic has Schafer. So now in Chapter 22,

they sneak into the monastery to rescue Schafer and stop Lazarevic. This

requires a lot of combat and platforming, as Drake and Elena work their way

through the monastery, fighting off soldiers as they go. They get to Schafer in

Chapter 23, but they’re too late. Schafer has been shot and left for dead, and

Lazarevic has the phurba and is off to find Shambhala. Schafer tells them that

the monastery hides the entrance to Shambhala, and as he dies, he implores Drake

and Elena to stop Lazarevic.

This further

underscores how high the stakes are in this adventure. So Drake and Elena

decide they’ve got to find a way to save the day. As they try to pull together

some sort of plan, they notice that there are yetis

loose in the monastery as well, adding to the challenges ahead of them. They

split up so Drake can get the Phurba and Elena can find the secret entrance.

Drake manages to find Chloe with the Phurba (with Lazarevic and Flynn nearby).

Using the Phurba and his notes, Drake is able to solve a tricky environmental

puzzle to find the secret entrance which is cleverly hidden in plain sight.

They manage

to sneak into the entrance and into Chapter 24. Of course, Lazarevic manages to

trap them in the entryway. Lazarevic threatens to kill Chloe and Elena if Drake

doesn’t help him. Under this coercion, Drake solves the puzzle that opens the

entrance and leads to some puzzle platforming with Flynn and some combat with

some yetis as well. Lazarevic enters and kills the yetis just as they’re about

to kill Drake and Flynn, and in looking at the corpses they discover that

they’re actually men, guardians of Shambhala (granted really strong men who are

extremely hard to kill). They now finally enter Shambhala, which is a large ancient

city overrun with greenery, and they’re immediately attacked

by more guardians.

RL: Chapter 24 gave us an opportunity to do something we hadn’t ever

done before: a sequence of play where Drake is accompanied by

someone with whom he is in an antagonistic relationship. Drake and Flynn still need to cooperate

to complete the sequence, but we had a lot of fun with the banter between them

as they travel through the area, and we hope it is another technique that helps

raise the emotional stakes as we race towards the game’s climax. We also took the opportunity to add in

another bit of finesse interactivity, as anyone who decides to take a swing to

Flynn’s irritating grin will discover.

It does add

a tension having to work with Flynn in this scenario (although I didn’t take a

swing until you mentioned it and I played through the sequence again). In the

following confusion of entering Shambhala, Drake, Elena and Chloe escape into

Chapter 25. Here you have combat with both soldiers and guardians as they try

to beat Lazarevic to the Cintamani Stone. Drake is now adamant about setting

things right (and saving the world). He’s become a hero, and it’s up to you to

succeed and save the day. As they make their way through the ruins of the city,

they notice more of the blue resin on trees, and when it’s shot it explodes. This becomes a way to clear a path as

well as a weapon to use against others. They work their way to a temple, and

solve some puzzle platforming which leads them to the

Cintamani Stone which is embedded in the Tree of Life. Drake starts worrying

that something is not right. He then figures out that the Stone isn’t a gem,

but is made of resin, that can be eaten to gain immortality (or at least you’re

pretty near invincible).

They then

spot Lazarevic by the tree, but before they can go, Flynn shows up, mortally

wounded and holding a grenade with the pin pulled. He sets off the grenade,

killing himself, leaving Drake and Chloe woozy, but severely wounding Elena.

Chloe ends up carrying Elena, while Drake goes to stop Lazarevic, and into the

final Chapter of the game.

At this

point in the plot diagram, we are firmly in the climax of the story, we’re out to stop the villain or die trying. Which

gives you a clear sense of where we are in the interactive diagram, deeply

invested and committed to successfully finishing this experience.

Drake moves

toward the Tree of Life and see Lazarevic drinking from the pool of sap. Drake

shoots at Lazarevic, but the bullets don’t see to have any effect, and he now

comes after Drake. In gameplay terms, we’re in the final boss battle, the

climax of the story. You then have to figure out how to kill Lazarevic (hint,

use the exploding blue tree sap) and once you’ve managed to catch him in enough

explosions, he weakens and falls.

Drake approaches Lazarevic, and Lazarevic calls him out on how similar they are

(look at how many people Drake has killed, just today even). But in the end,

Drake doesn’t kill Lazarevic in cold blood: he leaves him for the guardians. In

this moment, Drake makes the right choice and acts as a hero. And now, of

course, the whole city starts collapsing. So, Drake goes and finds Chloe and

Elena, and they manage to narrowly escape. You have a great scene where the

perspective shifts again, and you’re running toward the screen on a bridge

while everything collapses around you. This is another effective use of the

perspective as you really get to see the chaos all around you as you try to

stay just ahead of it at all and escape (to be honest it took me a couple of

tries) as we fade to black with Drake holding Elena, hoping she’ll survive.

And now

we’re in the denouement, the active gameplay is over (we won!) as we return to

the village and see Drake standing over a grave, at first it’s not clear if

this is Elena’s grave, but it turns out she did survive. Chloe says her goodbye

(they joke about playing the hero) and she encourages Drake to tell Elena about

his feelings for her, and Sully shows up to help with the recovery. The scene,

and the game, comes to an end with Drake and Elena joking about how much he

cares about her, as the boy (might actually) get the girl.

Meaning and

Mastery

With that,

we’ve completed the narrative experience of Uncharted

2. There is the multiplayer gameplay (which I have yet to experience) but I

want to discuss how the gameplay controls improved in this game as compared to

the first Uncharted. As I mentioned

at the start of this essay, I actually played a bit of the first game

initially, then played through all of the second, and then I tried to go back

to finish the first. But Naughty Dog didn’t rest on their laurels between the

two games. The gameplay controls have been refined and improved (in terms of

responsiveness and accuracy in both combat and platforming). So after playing all

the way through the second game, it was hard to go back to the first game with

the older controls. Interestingly, in talking with Richard about this, he noted

that the development of the multiplayer portion of the second game played a big

part in how they improved the controls.

RL: When we first announced that Uncharted

2 would have a multiplayer component, some internet-posting fans of the

first Uncharted were concerned that the single-player game of Uncharted

2 would suffer as a result of the fact that our attention would be divided

between two different parts of the game. As Drew says, it turned out that multiplayer actually helped our

single-player game.

In order to make the online multiplayer game as on-the-button

responsive as a great multiplayer game needs to be, we had to tighten up our

player mechanics and make them even snappier than they’d been in Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune, and this fed

back directly into a better feel for single-player, which used the same

executable (i.e. the same game code).

And this

made for a more playable game from my perspective, as I felt that I had better

control of Drake’s actions throughout the game. At this point, I want to take a

step back to discuss how the meaning of the game came through a mastering of

the gameplay mechanics across the experience of the story. In a well-designed game, the experience is kept pleasurably

frustrating; it’s not too easy, nor is it too hard. Ideally you get increasing

challenges followed by a reward, and possibly increased abilities that make it

a little less challenging for a bit, but then soon ramps up again.

Crawford (1984)

refers to this as a smooth learning curve in which a player is enabled to

successfully advance through the game. Costikyan (2001) notes that "play

is how we learn" and move from one stage to the next in a game.

Csikszentmihalyi’s (1991) notion of flow, in which a person achieves an optimal

experience with a high degree of focus and enjoyment, is an apt method for

discussing this process as well. And Gee (2004) notes that well designed games

teach us how to play them through rhythmic, repeating structures that enable a

player to master how to play the game. In terms of unit operations, the units

are being juxtaposed well so that the meaning and mastery builds as you play. I

believe this creates an aesthetic performative experience unique to games.

In Uncharted 2,

the developers do a nice job of striking this balance, on three levels. First

of all, the game has a fairly even mix of the two major types of gameplay

(combat and platforming) so that you are continually doing one or the other

(and often both) throughout the game. Second, there is a good flow to the

increasing level of difficulty across the game. It builds on your successes,

offering more daunting challenges. And finally, it blends the narrative and

gameplay quite seamlessly. The clever use of IGCs throughout the game helps

create the feeling of being an integral part of an amazing action adventure.

Combined together, the overall effect is one in which you start out as a bit of

a bumbling ne’er-do-well and as you play through this experience you become a

hero who saves the day.

RL: Thanks very much for

the kind words, Drew, and for the favorable comparisons to the academic work

around this subject. We worked hard

to create a structure for our game where the peaks and valleys of its

respective narrative and gameplay rhythms would be well-aligned, creating

synergistic effects for our audience of players.

We tried to create

patterns of rhythms that would be irregular enough to avoid the repetitive

feelings that some games suffer from. We feel like we did pretty well in this regard, with the exception of a

sequence of gameplay in the Monastery that doesn’t have quite enough story

beats to support the ongoing gunplay action, and where the pace of the game

starts to flag a little.

We also worked hard to

introduce the game’s mechanics in a way that would allow the player to learn

about them without ever feeling like they were being taught something. Our usual technique was to couch the

‘tutorial’ in terms of an action sequence, the opening train wreck ‘climbing

lesson’ being a good example. This

fed into a ramp of action where we offered successively more complex challenges,

building on the player’s previous experiences and the skills they’d acquired

from them.

We do our best to plan

these things in advance, but there’s also a good deal of iteration and

trial-and-error involved. We try to constantly put ourselves in the mindset of

someone who has never seen the game, and we do a lot of playtesting with people

who haven’t played before, to help us find and fix problems.

In truth, we use a lot

of gut instinct, too. As well as

the conscious approach we try and take to these issues, there’s also a little

bit of something intangible and unpredictable involved. So for me, when everything comes

together – as it did for Uncharted

2: Among Thieves - it makes the creative

process all the more satisfying.

Now that you

mention the Monastery, that actually still sticks out in my mind as the longest

gunfight (and I recall my wife mentioning it as well). This leads us into some

ideas on what good game design can do to create an engaging experience.

Ludic

Narrans

A good game can and should teach players what they need to know

and do in order to succeed. Ideally, the very act of playing the game should

enable players to master the gameplaying units of the gaming situation so they

can successfully master the rising challenges and complete the experience. If a

game gets too hard, too easy, too confusing, or if it just is too long and

seems never-ending, players may not finish. For these reasons and more, players

can reach a point where they drop off the curve and lose their sense of

engagement, becoming bored, frustrated and tired of playing the game. But if a

game enables players to stay on course and continues to hold their attention,

players will advance to a point where their immersion develops into an

investment in which they truly want to successfully complete the game experience.

And when there is a lack in the balance of the interactivity, the story can

actually help keep the player engaged in order to move from involvement,

through immersion to investment and successfully complete the game (Davidson,

2008).

RL: We’ve noticed from the

online data that we gather that about half our players complete the

single-player, narrative part of Uncharted 2. This figure is quite high for a

contemporary video game, which famously have poor completion ratios. We’d like to drive this number higher

though, in future.

This gets me thinking about the various reasons people play games (since

completion rates are normally low) and how some games are designed in such a

way to help make this happen. Uncharted 2 is an example of how a game can combine gameplay and story together in a

resonant manner. As I mentioned at the start of this essay, my wife actually

enjoyed watching me play through the whole game because she engaged with the

story experience, but only if I were playing on the “Easy” difficulty level

(the levels are Very Easy, Easy, Normal, Hard and Crushing). I usually play

games on normal, but I sometimes switch to easy depending on how a game fits my

skill level as well as the amount of time I have to devote to playing games.

Similarly, I will sometimes use GameFAQs when I get stuck for a while (again,

this depends on the amount of time I have to play the game). What was

interesting about Uncharted 2 was

that I started on normal and was doing fine, but the firefights took me long

enough (due to the number of enemies or the number of times I would die) that

my wife would lose interest in watching as she lost the thread of the

narrative, and didn’t have fun watching the seemingly endless firefight. But if

I set it on “Easy” this enabled me to advance through firefights more readily,

which kept the story beats coming at a pace that was enjoyable for her to

watch.

In talking with other colleagues and Richard, it seems that a lot people

enjoy watching people play this game. I think this says a lot about how well it

does blend the two together, and how games are becoming an even more