Plotting the Story and Interactivity

in Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time.

Drew Davidson, Ph.D.

MIT 4: The Work of Stories

In this paper, the experience of the videogame, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time , is analyzed by comparing two diagrams, one that illustrates the plot of the game's story and another that delineates the stages of interactivity. Performing a close reading of this game from these perspectives enables an exploration of how the game's story relates to the interactive elements of its gameplay.

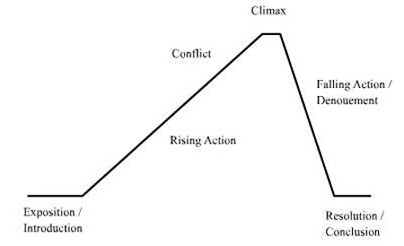

The first diagram used is a classic literary plot diagram.

Using this diagram, the story of Prince of Persia is explicated into its key moments across the experience of the game.

Next, a diagram illustrating the stages of interactivity is used.

This interactive diagram was developed in a previous paper, ( https://waxebb.com/writings/interact.html ) and outlines the interactive experience of playing a game. Briefly, the experience is posited to have 3 stages: involvement - being initially introduced into the game; immersion - becoming comfortable with the gameplay and the gameworld; and investment - feeling compelled to successfully complete the game.

The interactive diagram illustrates these three stages. The x-axis shows the relationship of the time spent playing the game, from start to completion. The y-axis shows both the level of interactive engagement (in purple), down from shallow to deep, and the percentage of game experienced (in green), up from none to all.

Comparing the results from both the above diagrams helps illustrate the relationship between the game's story and its gameplay and how they can fit together to create a satisfying interactive experience. Of course, this approach wouldn't necessarily be the most apt for analyzing all the different genres and types of games, but I think it is a fecund way to explore the Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (1).

The Prince of Persia is a classic gaming franchise that started out in 1989 as a 2D side-scroller with strong platforming elements of running, jumping and climbing through environmental puzzles. The Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (2003) represents a re-imagining of the franchise into an action-adventure game in the 3D realm. I chose this game specifically because of its overt attention to story and how it incorporates the act of storytelling into the experience of playing the game. I actually played the original game, but did not keep up with the franchise until this new release and have yet to play the latest release, Prince of Persia: The Warrior Within (2004). At the time of this writing, I have played through The Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time three times; the first time solely on my own, the second with help from GameFAQs to ensure I didn't miss any parts of the game, and the third mostly on my own, but with some references back to GameFAQs to doublecheck details. Each time took roughly 10-12 hours of gameplay in order to successfully complete the game. Also, I should note that all of my experiences are with the Nintendo GameCube version of the game.

With this experience under my belt, I feel comfortable analyzing the gameplay and narrative of this game. A quick aside: for those who have yet to play this game, this paper contains a lot of spoilers. I will progress linearly through my experience of playing the game and uncovering the attendant story. As I describe this experience I will try to clearly delineate the cinematic scenes that I watched as a spectator from the interactive scenes in which I was actively playing as the Prince.

The Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time starts with a short teaser animated movie before you hit any buttons. The movies slowly pans over a desert/oasis landscape that morphs into a woman asleep in bed. A raindrop plops into a puddle and the woman awakens. When you press "Start", you find yourself in control of the Prince on a terrace at night, light spills through the curtains from the room within. To start the game, you have to walk into the room, which triggers an introductory movie. Here you are shown a basic overview of the initial exposition that starts the plot. The Prince speaks in a voice-over discussing time, which he claims is not like a river, but more like a storm. He invites you to sit and hear a tale told like none you've ever heard. The Prince with his father, the King, and their army approach a city. A Vizier stabs someone and the battle starts as the King's forces invade the city. It seems that the Vizier and the King were working together. The Prince wants to impress his father by winning the treasure. He gallops his mount forward as the structure collapses and the Prince is thrown from his horse into the city. This scene ends with the Prince stating that he wants the honor and glory for his father. It's very economical with time, squeezing information in quickly before allowing you control to play. So in a short amount of time (no more than a couple of minutes really) you are enabled to start playing.

You now have direct control over the Prince character as gameplay begins. You have a very unobtrusive interface element with a crooked health bar in the upper left of the screen. Additional elements are added later as you progress through the game; such as the sand tanks and the power tanks that show the number of times you can manipulate time, and the round circle of time that shows how much time you can control. Plus when you get into fights with Farah (the daughter of the Sultan) at your side, her health bar appears as a red bow in the upper right of the screen. You immediately begin to see textual instructions on how to use the controller to direct the Prince's actions through the 3D game world. These instructions appear across the bottom of the screen for a short time and are in relation to the context of the actions you should be performing to best proceed. You are first directed on which analog stick controls the direction in which the Prince moves, and which stick controls the camera angle. The environment is rearranged by the battle around the Prince. The directions in which you are able to move become determined by the changing environments. These changes set up the platforming style of puzzling gameplay. In essence, you have to figure out how to move through the environments in order to proceed through the game. So while there is a feeling of open-ended choices, it is actually a linear game that uses environmental puzzles to direct your progress. So, you begin to learn the rather amazing physical abilities of the Prince as you can run, jump, climb and drop your way through the areas. Interestingly enough, you automatically climb small ledges (with no button press) but you are given instructions on which button to push to jump and which buttons enable you to climb up surfaces and drop from ledges. Often these types of actions and button presses are context specific; for instance, pressing the (x) button to drop only has an effect in the game if you have the Prince is in a position within the environment in which he can drop. Also, if you do nothing at all, the Prince goes into short animation cycles showing him looking around, stretching, etc. A nice touch that starts conveying the personality of the Prince. These initial textual instructions and the environmental context enable you to begin developing intuitive control of moving the Prince in this world.

At this point of the experience, a short plot exposition has been given and the player is in the involvement stage of interactivity, being introduced to how to play the game. It seems like common sense that exposition and involvement occur at first, but the Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time does a good job illustrating how to do this well. I think it's important to give a player some exposition in order to pique interest as involvement begins, but too much exposition for too long can be a distraction from involvement (especially if it's a long scene that does not allow a player to skip it all). Concurrently, it's crucial to afford the player the opportunity to play as quickly as possible so that the interactive experience of the gameplay can start.

The start of the Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time has a rather short moment of control (walking the Prince into the lit room) which may seem extraneous, but enables you to actively begin the game in context. The introductory movie is short and informative and quickly drops you directly out of the cinematic and into a contiguous playable environment. This experience gives the player a nice introduction into the gameplay elements with specifically designed environmental challenges and corresponding textual instructions that help guide you into moving through the world.

Back in the game, you quickly discover that the Prince can run up and across spans of wall as well as jump and climb. You are also shown how to break through small barriers with your sword. Often there will be quick cinematic cuts when you perform exciting physical feats: the camera launches out and gives you a dramatic view of the Prince in action (sometimes in slow motion as well). And when you happen to die by not successfully completing an acrobatic feat, the Prince speaks in voice-over saying, "Wait, wait . . . that is not how it happened... Now, where was I?" and you are reset to the spot right before you accidentally leapt to your demise (more below on distinctions of this experience as you gain some control over time). These voice-overs continue the development of the Prince's character, and they also foreground that this experience is a story the Prince is relating. Another example of this is when you pause the game, the Prince asks, "Shall I go on?" and when you resume play he says, "Then I shall continue."

Now, after successfully completing a series of environmental puzzles the player begins to reach a point of familiarity with the control schema for platforming in the game. Next you are gently introduced to your first battle. I say gently, because it is a very easy fight against one soldier, filled with textual instructions on how to use the controller to enable the Prince to attack, dodge and block. You see the enemy first and as you approach you get quick little cinematics of the enemy posturing that serves as an alert to the change from platforming to fighting.

Again, there are some cinematic cuts that dramatically show your fighting moves, but there is a difference with these cuts in comparison to the platforming cinematic cuts. The fighting cinematics can actually interfere with the gameplay during fights; whereas, I never had such problems with the platforming cinematics. During fighting, when the camera launches to show a different view and then zooms back to fighting, I often lost a sense of direction in relation to where the enemies are located and so there is a moment needed to re-orient myself within the action. In these instances, the cinematic camera effects interfere with the gameplay, while during platforming they add a sense of drama to what you are doing as the Prince.

If you are hit during fights, your health bar will reflect the damage. This gives you a sense of how you're managing the fight. Once you vanquish your foes, you can sheath your sword or it will occur automatically, which is a nice visual indication that the fight is over and you are moving into the platforming elements of the game. This makes a clear distinction for the player about the two major types of gameplay (platforming/puzzling and fighting) that alternate throughout the rest of the game.

Next, you come upon another fight (this time with two soldiers); like the series of initial platforming puzzles, you are being thrown several small fights in a row. This is a great contextual in-game tutorial of the gameplay elements that helps the player proceed through the experience of playing this game. After this fight, you are introduced to the element of controlling your health. This is done by drinking water from any of the fountains around. You get a quick cinematic of the Prince drinking (with a little trill of music). When you drink, your health bar is replenished to full (the time it takes depends on how much damage you've received).

A rhythm of the gameplay is beginning to develop in this experience, an alternation between fighting and platforming. At this time (about 10-20 minutes into playing) the immersion stage of interactivity is beginning. No new information towards the plot has been revealed, although with the voice-over asides there is a sense of character development with the Prince and his desire to win the treasure. Along with these voice-overs, the general action of fighting and progressing through space carries the experience forward. So, the foundational gameplay elements have been covered and familiarity with the interactive experience is developing.

A new wrinkle is introduced with the addition of contextual cinematics that occur when you enter a new area. These cinematics give an overview of the area (which feels somewhat akin to a short level) panning away from the Prince to the exit of the area and back across; showing the environmental puzzles or the enemies or both, and giving a sense of what needs to be done in order to progress (the mission in this level as it were). You also reach the first save checkpoint. The Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time uses the mechanic of checkpoints spread out across the environments to enable a player to save the game progress (more below on the development of the method established for these checkpoints that differs from the first checkpoint). Each time you reach a checkpoint there is the option to save, quit, or continue and the storytelling element is foregrounded again with the Prince asking, "Shall I continue my story from here the next time we're interrupted?" When you save, he says, "Done, I'll start the story from here next time." If you choose to quit, the Prince asks, " Do you wish me to leave before finishing my story?" and if you choose 'yes' he says, " As you wish," if you choose 'no' he says, "Then I shall continue." Each checkpoint is named (e.g. The Maharajah's Treasure Vaults, Atop a Bird Cage, The Hall of Learning , etc.) and this gives a sense of chapters in a story as well as a narrative flourish to the game's menu mechanics. Also, the general Pause menu enables the player to continue playing, go into game options (sound, display, camera, controller) or quit.

You are now fully using the gameplay mechanics learned so far to navigate through these environmental puzzles and fight through enemies, and a new element is added. Moving defenses (saws and rotating columns with hooks and such) require an increase in the skill with which you need to perform in order to get through the rooms, courtyards and areas. Concurrently, the plot moves into rising action. You watch a cinematic of the magnificent treasure, the hourglass and the dagger of time, and the Prince's voice-over urges you to get the dagger. This requires some intricate puzzle platforming through the environments.

You arrive at an extensive cinematic cutscene that distills some plot information much like the introductory movie did. You get the dagger of time and watch the Prince push the button on the handle and reverse the flow of time, which enables him to escape the collapsing ceiling. After short bit of gameplay in which you exit the room, the cinematic shows the victorious King take the spoils of war, including the hourglass and slaves (the woman from the teaser trailer at the very start of the game is in this group). The entourage journeys forth to Persia, and then enters a grand ballroom where the King presents the recently won treasures to the Sultan. The woman from the group of slaves is seen hiding up in the shadows. The Vizier gets the Prince to release the sands of time from the hourglass by inserting the dagger into the hourglass. This causes an immediate and immense sandstorm to erupt and the sands swirl around, turning everyone touched into zombies. In the chaos, everyone rushes to flee, and the mysterious woman manages to escape.

The Prince turns to fight the approaching zombies and gameplay is resumed. In a voice-over he explains that he realizes that he was spared because he held the dagger. He goes on to say that he believes it is with the dagger that he can liberate these zombies from their walking death. For the first time, you are fighting zombies instead of soldiers. As you strike them down, you hear the woman yelling out to use the dagger to absorb the sand from them so that they evaporate and stay down, otherwise they rise back up to fight more. So, you now receive some gameplay hints from characters within the context of the game itself as well as receiving textual instructions on how to use the dagger. You also see up in the interface the addition of small circles that begin to fill up as you capture sand from the fallen zombies and you get instructions on using the dagger to shift time and freeze zombies. This is the introduction of another interesting gameplay mechanic, the ability to control time. An ability that comes in quite handy as you progress through the game.

As you fight, you see a column of light forming in the room with you. Once you finish this fight with zombies, a cinematic starts immediately. The woman runs away and the Prince walks into the column of light. A rapid sepia-toned vision flashes by showing the Prince performing acrobatic feats and fighting more zombies. You are then asked if you would like to save or view the vision again (these columns of light are how checkpoints are marked throughout the rest of the game). So, saving only occurs after successfully completing a fight which causes these lights columns to develop. Your reward is the opportunity to save. Once you save and return to play, you see a brief cinematic of the Prince waking up beside the column of light with a voice-over assuring you that the horrors he is relating are true. You then walk into a room that you just saw in the vision. So it's apparent that the visions give you a glimpse of the near future while at the same time serving a gameplay purpose of giving you a sense of what you are supposed to do in order to proceed.

Following this significant cinematic, the plot is fully into rising action as the shape of the conflict becomes apparent, with the Vizier as the major villain in the story. Also, the immersion stage is firmly engaged as the rhythms of gameplay are established and the player truly has to use all the skills learned in order to win the fights and solve the environmental puzzles.

Back in the game, you exit the ballroom through the gate that the woman ran through, and she is just ahead of you (the Prince yells out for her to wait) but the ceiling collapses and you can't follow her, so you have to enter another room. Here is where you first see a little shining pile of sand that you can absorb with your dagger. This helps add more sand to the dagger so you can control time more. These little piles will be sprinkled around environments from here on out. You now have some environmental platforming to do in order to proceed to a point in which you reach another fight with zombies. After successfully completing this fight you get a column of light (a save checkpoint) but with this one, you get to direct the Prince into the column in order to save your progress through the game. When you walk into the column you see another vision of the future ahead of you.

As you proceed through these rooms, you come to one of the few times in the game in which you actually can get a little off the linear progress of the game (a fork in the path). You have the opportunity to continue dropping down some rubble, or going through a hole in the wall. If you choose to go through the hole you find yourself running down a hall with sheer curtains that you pass through as it slowly gets darker and fades to black. Next, you are in a magical world, with ethereally lit bridges that you cross to a central fountain with shimmering water. As you approach, a cinematic takes over showing the Prince drinking the water. Whispering tones accompany his entranced look as the scene fades to black again. You are then returned to the moment right before you entered the mysterious hallway. The hole in the wall is now gone and your health bar increases in length. In a voice-over, the Prince says that he feels better than ever before. So now the player has the challenge of finding other potential "forks in the path" that enable an increase in the Prince's health, which really helps as the fights and platforming get more difficult throughout the game.

As you continue, you get a quick cinematic when the woman pulls the Prince aside, introducing herself as Farah, daughter of the Sultan. She wants the dagger, and the Prince doesn't trust her and he won't give it to her. The camera focuses on her scarab necklace (possibly hinting as to why she survived the sands of time). As they talk, large scarabs approach. The conversation abruptly ends with the attack by the scarabs and the Prince yells to Farah to run. You are now back in control and can quickly fight off the scarabs. As you continue on, you come out to an open courtyard; it is night, and another short cinematic reveals several large birds winging the hourglass up and away, seemingly toward the top of a tall tower.

Next, a new facet in the gameplay is introduced; handles that you have to pull in order to open a way forward, but that also engage some time-based mechanism (e.g. a door that slowly closes as you race to get to, and through, it). This first handle task is relatively easy, you pull the handle and a bridge extends for you. You have to run across the bridge before it retracts completely. Now you've arrived at one of the more unique puzzles in the game. A guard up in the distance yells for you to help him activate the defense systems to thwart the monsters. It's a task that requires both of you, but mostly you. You are in the middle of this round cylinder of a room on a round platform that you can raise and rotate. You need to pick up four long axles in the proper order so that you can raise and rotate them through a maze of channels in the wall of the cylinder and insert them correctly to activate the defense systems. The guard, like Farah before, yells out general instructions and encouragement. Finally, you both pull hanging levers, and then the guard (out of sight, but not out of sound) is attacked by zombies and you hear him die. Puzzle solved, you now have to fight more of these zombies to continue onward.

This puzzle is interesting in two ways in regards to the story and gameplay. In terms of gameplay, a player has to complete it in order to progress. With the story, it serves as a moment where the Prince meets another survivor and they work together to thwart the zombies. But after playing through the game a bit more, I realized that these defense systems are somewhat disingenuous. They really just set up more challenges for a player, with more saws and blades to avoid as the player moves forward. On the one hand, hindsight made me wish that I had not activitated the defense systems. On the other hand, the game only advances when the puzzle is successfully solved. It is through this moment of story that new facets of gameplay are explained and introduced. Also, I found it wonderfully engaging and immersive to be in the role of the Prince and wish that I had not done something. At this moment, the story elements were actually helping me become more immersed in the experience of the game. I regretted a gameplay action I had to take and now had to suffer the consequences of solving the puzzle and navigate through all these defense systems that I brought on myself as the Prince.

Back in the game, you now have your next handle to pull. This time it is a little more difficult than the first, as you have to run and jump through moving buzzsaws, spikes in the floor and moving spiked columns. The game continues to ratchet up the elements involved in the platforming aspects of the game, causing you to advance your mastery of the gameplay mechanics. In keeping with this, you now find levers you have to jump up to pull, as well as switches high up on walls that you have to push, each adding a little wrinkle to how you go about puzzling through the environment. Interspersed throughout are several battles that you fight through, which also ratchet up with different types of zombies (guards, dancers, large imperial guards, etc) and more advanced fighting moves, as well as plenty of water to drink to keep your health up. You also find another branch that allows you to lengthen your health bar so that you can better survive the trials ahead.

At this point (roughly around 3-4 hours of gameplay) the story is continuing along the rising action. It seems a potential ally, Farah, has been introduced, and large things are afoot as the hourglass has been absconded with. In terms of gameplay, the immersion stage is well established, the game has a solid a rhythm of fighting and platforming with wrinkles in both, and the helpful addition of the ability to control time (rewind, slow down or speed up time). So the player is using all the skills learned to survive longer fights with a variety of zombies that require fighting in different ways to defeat them. Also, the player is navigating through more extended sequences of platforming with more intricate challenges to maneuver in order progress forward through the game. Again, this would seem to be exactly where you would want to be as a player, but the Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time has done a good job of mixing these variables together to continue challenging you as you progress. The experience is kept pleasurably frustrating; it's not too easy, nor is it too hard. Chris Crawford refers to this as a smooth learning curve in which a player is enabled to successfully advance through the game (Crawford, 72). Greg Costikyan notes that "play is how we learn" and move from one stage to the next in a game (Costikyan, "Where Stories End and Games Begin"). Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's notion of flow, in which a person achieves an optimal experience with a high degree of focus and enjoyment, is an apt method for discussing this process as well (49). And Jim Gee notes that well designed games teach us how to play them through rhythmic, repeating structures that enable a player to master how to play the game (Gee).

I mention these ideas because I soon reach a point in the game in which I feel this balance is lost somewhat. In a cinematic, the Prince returns to the large ballroom from which the sands of time were unleashed. Farah is already there, bow and arrow in hand, fending off many zombies. The Prince races to her side and discovers that one of the zombies is recognizably his father (a big point in the story indeed). You are immediately dropped back into gameplay in one of the toughest (and longest) fights of the entire game. I find it somewhat fitting that this pivotal point in the story (a fight with your zombie-father) is such a grueling affair. Also, it is your first fight with Farah's support. You see her healthbar in the upper right, and she shoots at the zombies from afar. You are now responsible for keeping her alive during fights, so this adds to the challenge as well. Although during this fight, the space is large enough that you can move away from her and the zombies chase after you.

That said, this fight is also significantly longer and tougher than proceeding fights, enough so that I almost quit playing the game entirely the first time I reached this point because I had such difficulty successfully finishing this fight with wave after wave after wave of zombies. This is one of the first fights where the zombies combine attacks more, and often I ended up knocked to the ground with four zombies surrounding me, attacking until I died. The first time through it must have taken me a dozen or so tries to finish it, the second time probably two or three, and the third time another four or five. Again, I find some resonance between the gameplay and the story with this being a difficult fight with your zombie-father (who takes forever to dispatch), but it was really close to being too hard, and I found myself slipping out of an immersion stage and into wanting to quit. Yet, I had enough time invested and enough skill development from the proceeding experiences, that I was always able to eventually win this fight (each time I did, it was more a sense of relief than anything else). So, this was the first time during the game that I felt the balance was a little off, the challenge was maybe a bit too extreme, but it wasn't insurmountable and I was able to get back into the gameplay and story as I progressed.

Once you do finish the fight, you have a cinematic in which the Prince rips off his sleeve in order to bind a wound on his arm (he slowly loses his shirt throughout the game, his wardrobe showing the effects of the difficulties he is facing). The Prince then walks directly into a light column with Farah protesting as he does. Directly following this save checkpoint, a cinematic shows the Prince and Farah agreeing to work together to get to the top of the tower where the hourglass is located and try to put an end to this madness. Farah seems to know how the dagger needs to be used in order to return the sands of time back to their proper place within the hourglass. So you have a direct gameplay goal (to the top of the tower!) related to you through the story.

The story and gameplay align again as Farah is now definitely an ally, which means a new facet for the player in both fighting and platforming. With fighting, she is now a part of it, so the player has to protect her during these fights. With platforming, the player now has to puzzle through in ways that enable her to move along with you. She can't jump as far or as high, but she can squeeze through cracks and tunnels that the Prince is too big to fit through. So the sense of working together is heightened as you literally have to work with her now to puzzle through the environments. I should note that you are never in control of Farah as a character you can play. The story is related from the perspective of the Prince continually throughout the experience and he is the only character you get to control.

Back in the game, the rhythm is quickly reestablished as you platform and fight your way onward. The platforming gets more challenging not only because you are working together with Farah, but you are beginning to work your way up towards of the tower, so you begin having more and more chances to fall to your death (which can be reversed with control of time, but only as long as you have enough sand in your sand tanks). You now get attacked at times by large birds and bats, which try to knock you to a fall. Also, you can continue to find and follow branches that enable you to extend your healthbar. You have many puzzles that you work in coordination with Farah, and many tough fights throughout. Along with the increase in health, you can find newer, better swords that are more powerful and enable you to break through more things and deal out more damage to zombies. This really helps as the fights get harder and the types of zombies get tougher to beat as they get larger and more coordinated in their attacks.

A really nice touch throughout the game is the variety of environments. The art direction of the palace grounds, full of rooms, courtyards and such, is shown through a variety of color palettes, as well as different types of environmental challenges. For example, you navigate through a warehouse, an aviary, high cliffs, royal baths, etc. This variety gives a sense that progress is being made and helps keep the game from feeling repetitive. Concurrently, the sound design complements the visuals, with a variety of soundtracks, all touched with a middle eastern feel and specific to situations (i.e. fights scenes have more of a pounding element, whereas beautiful outdoor scenes are more ambient). Also, the sound effects of the in-game actions add to the experience; crumbling rocks, the swish of the Prince's sword, and the sounds of combat (although I found the shrieks of the zombies to be annoying, especially during long fights). And the vocal talent is quite good, conveying a sense of personality for the characters. The visuals and audio combine together to give a nice magical Arabian Nights feel to the experience.

The immersion stage is solidly engaged with the rhythmic gameplay, and the rising action is now directed toward a specific goal, the hourglass at the top of the tower. As Greg Costikyan notes, a game should require decision-making and management of resources in pursuit of a goal ("I have no Words..."). This adds to both the story and the gameplay. A fun little easter egg occurs during this part of the game. Easter eggs are little hidden secrets that you can ferret out and often give you bonus material. In this game, you come to a rotating switch; a 90 degree rotation opens the gate and you can go through, but if you rotate it 90 degrees more and then break down the wall (which looks solid) you open up a hole and unlock a playable version of the original, 2D Prince of Persia game. You can save your progress in the Sands of Time and start playing the original game, or you can now access the original game from the main menu.

Back in the current game, daybreak arrives, giving a nice sense of time to the proceedings and further appreciation for the indefatigable Prince. You continue on with more platforming and fighting. During this part of the game, you come to an interesting cinematic after a checkpoint save. The Prince wakes up with his head in Farah's lap as she calls him her love. The Prince immediately jumps up in a bit of confusion, and you're back into gameplay with a love story in the air. Shortly thereafter you have a new type of puzzle; pushing mirrors around to reflect light throughout a room in order to hit a crystal with a beam of light. You continue onward with Farah until you reach a point where the floor collapses out from under you, causing a cinematic to kick in where the Prince falls, blacks out, and then wakes up alone in the filthy dungeons. The Prince rips of his ruined shirt and now goes bare-chested for the rest of the game. You are separated from Farah, so finding her has now become a plot point and a gameplay goal.

You work your way up out of the dungeons, fighting and platforming your way back to Farah. When you do get up and out, you find her in the midst of a fight, where you join in to help. After this fight, when you save you have an interesting vision in which you see Farah taking the dagger of time. In a cinematic, the Prince wakes up and becomes a little bit distrusting of Farah, complicating the love story. And so the rising action of the story is in full swing and the investment stage of interactivity is beginning as the end of the game is in sight. You've been playing for about 8-9 hours, and with this complication related, the player has now reached the huge tower in which the hourglass sits at the top. The end of your goal is in sight, you just have to make it to the top.

And here is the second time in the game where I feel the balance is a little off, but again I think it also fits within the framework of the story. As you enter the bottom of the tower you come to a small round room, and Farah runs in so you have to follow. The gates slam shut and the room begins to rise. As it rising, some of the biggest, toughest zombies arrive. This fight is by far the longest, toughest fight of the game. And since the area is so small, a huge part of the challenge is keeping Farah alive as you can't draw the zombies away from her. Instead you have to fight and fight and fight. This fight serves as the penultimate rising action as you literally rise up to the climatic moment of finding the hourglass. And so, in terms of the story it's like the fight against your father-zombie, a major moment in the plot.

In terms of the gameplay this fight took me forever to successfully complete. Like before, I almost quit playing the game because of it. What I found disturbing about this particular moment of imbalance was that it came right when I was feeling almost destined to finish this game. The game had given me the "illusion of winnability," and I thought I was going to have a successful ending (Crawford, 73). I had made it to the tower (finally!) and I could sense the climax of the story. Yet, during my first attempt, it took me about a dozen tries. The second time took five or six tries, and the third, another dozen. It was extremely frustrating to have it be this hard, but here is where the story really helped keep me invested in successfully completing the experience. If it weren't for the plot development and the rising action causing me to want to reach the tower and finally get there, and then really, really want to reach the top of the tower, I would have quit. I wasn't enjoying the gameplay at this point (it was too difficult and endless a fight to really keep me invested) but I had so much time and experience invested in the story that I persevered and managed to win (again with a huge sense of relief more than anything else).

Although he story also helped give me a huge sense of accomplishment, I had made it to the top and to the hourglass. Then a twist in the story comes at an odd moment. As you leap atop the hourglass, getting ready to insert the dagger, control is taken away. I was at the climatic moment where I was going to win, and a cinematic cuts in, adding a plot twist. Instead of successfully completing the quest, the Prince hesitates. The Vizier appears, summoning a sand storm that whisks the Prince off the hourglass and sends both he and Farah tumbling away into the darkness.

You wake up in control of the Prince and walk down an extremely long winding staircase and come to an interesting little sound puzzle. You are in a round room full of doors and Farah is calling to you. You can enter a door, and you'll just pop back out another one in the same room. The trick is to enter the doors from which you hear the sound of water. As you work your way through the doors you'll eventually find Farah in a bath and a seductive little cinematic hints at the culmination of the love story.

You then wake up alone, back in control again, but Farah is gone and you have neither your sword nor your dagger. You have just watched a climatic part of the story, now you've come to the climatic part of the gameplay; some amazingly intense platform puzzling with no dagger, so you have to do this without any time control. You are high up with ample opportunity to fall to your death and no way to reverse time, so you have to really display your mastery of these gameplay mechanics to puzzle through these environments. Also, zombies are coming and you have no sword, but you immediately are presented with a final light and mirror puzzle that once you solve wins you your final sword which is so powerful that one blow eradicates zombies. So fighting becomes different as well, it's a little easier, but again, with no dagger you now have to be more careful.

Once more you aim for the top of the tower, but this time you climb up the outside of the tower, which presents the challenging climatic platforming of the game. Like the climatic fight, the climatic platforming is really difficult. Unlike the fighting, I felt amply prepared for this challenge and believe it was a fair test of my mastery of these elements of the gameplay. Also, while I think that the climatic fight had some plot resonance, in the end it's just a really, really long fight. The climatic platforming also takes a long time, but it seems to have a more harmonic resonance with the plot development because the player is physically moving toward the game goal and rising up to the climatic plot point of getting to the top of the tower. Even so, it probably took me a dozen tries each time I played through the game in order to successfully get to the top. Once you (finally) get to the top, a cinematic shows Farah fighting with the dagger of time and then she falls. The Prince runs and catches hold of the dagger, they both hold the dagger for a second and then she falls to her death.

You are back in control of the Prince and have to fight off the zombies who killed Farah. You then make your way back to the hourglass where she lays dead. In a cinematic the Vizier shows up, but the Prince runs up and plunges the dagger into the hourglass. Now, I didn't really mind losing control the first time, since there was a plot twist revealed, but to take away the climatic moment again was definitely a disappointment. It would have been a really nice alignment of story and gameplay to allow the player to insert the dagger into the top of the hourglass and then cut to a cinematic. That disappointment aside, the cinematic shows all the time and experiences up to now being rewound in a whirl completely back to the very beginning of the game. The Prince wakes up back in camp with his Father prior to the invasion of the city where Farah and the Vizier live. He is back in his pristine outfit, but he has the dagger of time. He sneaks into the palace up to the terrace where the player starts the game. It's now apparent that this is the terrace into Farah's room (who at this moment in time has never met the Prince). The Prince enters and offers to tell her (you) a story...

...The story of the game you have just played through (which now has never happened yet). The denouement is now quickly rushing toward the conclusion of the narrative and the investment stage is firmly engaged as a successful end seems extremely likely. All of the little storytelling asides become more than just little affectations and show that the whole experience has been the Prince telling his story to Farah (you). The start of the game was actually the Prince walking in to tell her a story. It's a wonderful moment of frisson as you realize that your time with the game (around 10-12 hours of playing) has been whirled away within the context of the story. And this moment has some post-structuralist, self-reflective facets as well. I believe that it's through stories that we relate our gameplaying experiences. These stories contextual our virtual experiences; for on the one hand, we are sitting on the couch, pushing buttons in a coordinated manner, but on the other, we are the Prince of Persia, saving the day. And the gameplaying experience of the Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time is contextualized as a story that the Prince is telling Farah, a story of his "virtual" experience that has now never happened, but he did indeed save the day. And it is at this moment when you realize that while you have been playing the role of the Prince throughout the game, you have also been positioned as Farah listening to the Prince tell this story. This moment illustrates how the interactive experience of a videogame can make manifest a theory of reading in which the reader is just as active a creator in the meaning of the text as the author. You are both the "author" of the story (the Prince) and the "reader" of it (Farah). Your actions as the Prince are also your imagining of the story being told to you as Farah. It is an elegant twining of story and gameplay together in this interactive experience.

Back in the game, the Prince finishes the story and the Vizier shows up wanting to kill him so that he can try to unleash the sands of time again and have them at his command. You now have control of the Prince and fight the Vizier. He performs some magic, sending three shades of himself that you have to defeat before you can actually fight him. This is a ridiculously easy fight, especially compared to the climatic fight going up the tower. You can quickly dispatch the Vizier, a necessary fight as he was the primary villain, but one that proves to be the last small part of a larger journey which has already occurred. This leads to the final cinematic, the resolution of the story and the successful conclusion of the game.

Back on the terrace, the cinematic shows the Prince return the dagger of time to Farah for safekeeping. She now realizes that he has averted a war by killing the Vizier who was going to betray her kingdom. Farah asks why he told her such an absurd story and the Prince tries to kiss Farah but she pushes him away in anger. The Prince uses the dagger to rewind time to right before the attempted kiss, and then agrees with her that is was indeed just a story. Much wiser from his experience with the sands of time, he gracefully bows out, leaping up and at her request giving her a name to call him (a name that I won't reveal here so as not to completely spoil the entire game for readers of this paper). And with that, Prince of Persian: Sands of Time comes to an end.

In reflection, I think the dual approach of analyzing the story plot and interactive levels enabled me to show the moments in this game when both elements were working together to truly engage me in the experience. It was also a useful perspective for exploring moments throughout the experience that didn't work as well as they could have . Overall, the story development and the rhythmic gameplay help players understand the gaming situation, the "combination of ends, means, rules, equipment, and manipulative action" required to play through the game (Eskelinen). That said, I kept my analysis with both diagrams at a general, high-level progression of the plot and the stages of interactivity. I think this was useful, but I also believe it could be interesting to get more granular with both diagrams and really dig into the details of the diversity of peaks in valleys in the development of the plot of the story as well as the moments of engagement, disengagement and reengagement that occur during the progressive stages of interactivity. I think both macro and micro perspectives would be worthwhile to pursue in analyzing interactive experiences.

A good game can and should teach players what they need to know and do in order to succeed. Ideally, the very act of playing the game should enable players to master the gaming situation so they can successfully master the rising challenges and complete the experience. If a game gets too hard, too confusing, or if it just is too long and seems never-ending, players may not finish. For these reasons and more, players can reach a point where they drop off the curve and lose their sense of engagement, becoming bored, frustrated and tired of playing the game. But if a game enables players to stay on course and continues to hold their attention, players will advance to a point where their immersion develops into an investment in which they truly want to successfully complete the game experience. And when there is a lack in the balance of the interactivity, the story can actually help keep the player engaged in order to move from involvement, through immersion to investment and successfully complete the game.

As Lev Manovich notes, when engaging new media (or playing a game), we oscillate "between illusionary segments and interactive segments" that force us to "switch between different mental sets" demanding from us a "cognitive multitasking" that requires "intellectual problem solving, systematic experimentation, and the quick learning of new tasks" (The Language of New Media, 210). So, when the story is effectively intertwined with the gameplay, the rising action of the plot can parallel the rising challenges of the gameplay, and enable us to have a compellingly engaging experience. While the story in the Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time was mostly related in cinematics, there was an attempt to inject it into gameplaying moments through the Prince's voice-over asides, and certain pivotal actions the player has to take that move the plot forward. And the gameplay is influenced by the story in the way characters share advice on what to do and how plot points become gameplaying goals. The Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time may have had a few faulty moments of dissonance, but overall, it did an elegant job of combining its narrative and gameplay to provide a fulfilling interactive experience.

References

Costikyan, Greg. "I Have No Words & I Must Design." http://www.costik.com/nowords.html

---. "Where Stories End and Games Begin." http://www.costik.com/gamnstry.html

Crawford, Chris. "The Art of Computer Game Design."

http://www.vancouver.wsu.edu/fac/peabody/game-book/Coverpage.html

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience . New York: HarperCollins, 1991.

Davidson, Drew. "Interactivities: From Involvement through Immersion to Investment."

https://waxebb.com/writings/interact.html

Eskelinen, Markku. "The Gaming Situation." Game Studies, vol.1, issue 1, July 2001.http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/eskelinen/

Games and Storytelling. http://www.gamesandstorytelling.net/

Game Studies. http://www.gamestudies.org/

Gee, James P. "Learning by Design: Games as Learning Machines," Paper presented at the Game Developers Conference, San Jose, CA. 2004. http://labweb.education.wisc.edu/room130/PDFs/GeeGameDevConf.doc

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media . Boston: MIT Press, 2001.

Montfort, Nick. "Story and Game." Weblog post: 2005/03/16.

http://grandtextauto.gatech.edu/2005/03/16/story-and-game/

Ryan, Marie-Laure. Narrative as Virtual Reality . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2001 .

Note

1. I should note that I am fully aware of the seminal discussions around ludology and narratology as relates to the study of games. For more on this discussion, Nick Montfort posts a nice summary of the ideas involved, and both the Game Studies and Games and Storytelling websites cover this topic in depth (all of these are listed in references section below). Currently, the discussion seems to be evolving across theory and practice to a categorization of the various perspectives from which people are studying games with three broad and blurred groupings emerging; game studies (in which ludology would be found), interdisciplinary (in which narratology would be located), and vocational (how to actually make games). I believe it is useful to consider games from a variety of perspectives; in doing so we can, as Marie-Laure Ryan notes, observe features that remain invisible from other perspectives (Narrative as Virtual Reality, 199). So, for a game that has a strong storytelling theme like the Prince of Persia: Sands of Time , the approach in this essay seems fitting.